LAST TRAIN to FREEDOM:

A Young Jewish Family’s Escape from Behind the Iron Curtain

available at Your Favorite Book Seller today

About the author

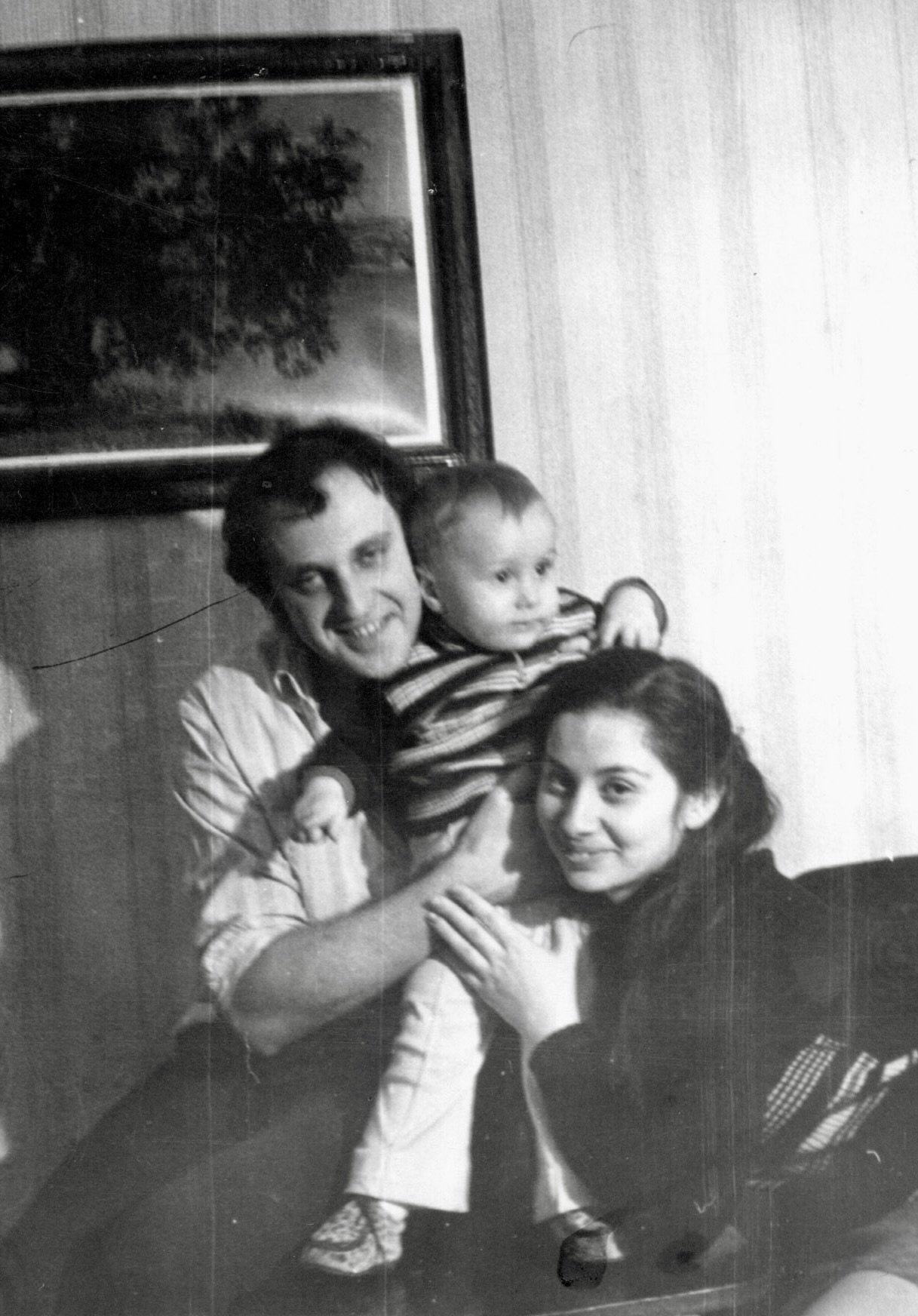

Galina Cherny was born and raised in the capital of Soviet Ukraine—Kiev. In 1979, she emigrated to the United States as a Jewish refugee with her husband and their three-year-old son. Galina was twenty-six.

She began her professional journey in Los Angeles, where the family settled upon arrival. Starting as a simple clerk with very limited English proficiency, she later became a computer programmer and ultimately ascended to technology executive leadership and later became a transformational leadership coach, founding her own boutique firm, The Cherny Group.

Galina is a gracious hostess who enjoys bringing people together in her home in Encino, California where she lives with her husband John. Galina and John enjoy travel, dancing, and the outdoors. But most of all, they love spending time with their two sons and their families. They have four grandchildren, whose very presence lights up their lives.

Galina is a passionate storyteller whose childhood dream of becoming a writer materialized with her memoir, The Last Train to Freedom.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Galina Cherny’s debut memoir is a riveting account of her young family’s daring escape from the barbed-wire borders of the Soviet Union to the United States of America. It’s a tale of growing up in the USSR as a Jew, and a love story that begins with no promise to survive.

The Last Train to Freedom is a raw, honest, and personal account of a young woman's journey from living a life of obedience in a closed society, where existence was predetermined by the government, to learning how to embrace the life of possibilities, risks, and choices.

Galina’s is a moving story of triumph against all odds. A tender tale of love, courage, and gratitude.

It all started when…

An unexpected blind date on a balmy May evening in Kiev in 1974 changed everything, opening Galina to love and the possibility of a life of freedom and opportunity. To follow love, she would have to leave everything behind. But first, she must conquer her own doubts and the terrifying guilt of betraying her family. And her country.

Praise

“‘Last Train to Freedom’ transports us from the 1970s Soviet Union to sunny California as Galina Cherny recalls the ordeals of living in the USSR and emigrating from there during the height of the Cold War. Now fluent in English, and a spirited writer, Cherny reveals what life was like behind the Iron Curtain and the challenges and shocks she and her family faced in the US—a nation she fell in love with. Historians and casual readers will find her tales informative, fascinating, valuable, emotional, and inspirational. I’m glad I read this book!”

“As an American Jew whose family emigrated to the U.S., your story had special resonance for me, and I enjoyed soaking up all the rich details you provided.”

“An extraordinary insight into the fight for freedom; each page will take you on a journey as beautiful and profound as the author’s own.”

“I LOVED your book. I cried at several points while reading it, and that is truly one of the biggest compliments I can give an author.”

EXCERPTS & THOUGHTS

Holocaust Remembrance 2023

In honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day, here is a FRAGMENT from my memoir, LAST TRAIN TO FREEDOM. Assembled with snippets of information collected over time, below is a personal narration of WWII events that have impacted my family. But the story of my family is also a history of 9.5 million Jews living in Europe at the time—those who miraculously survived the atrocities and the 6 million who perished at the hands of the Nazi extermination machine.

2

FAMILY QUILT

... On June 22, Chernobyl family vacation planning turned into a nightmare. Rumors of the treatment of Jews in the Nazi-occupied territories suddenly created a genuine panic among the Soviet Jews. It became apparent that fleeing Kiev toward central Russia—the opposite direction from Chernobyl—gave a chance of survival from a lethal fate to the Jewish women and children. …scared, confused, and shocked under the relentless barrage of bomb fury… the family prepared for evacuation…

...Godl and the children returned to Kiev a week after the family had left. They evacuated Kiev to Krasnodar Krai (in the North Caucasus region in southern Russia) and not to Ural, where the rest of the family settled. [It is there, my great-grandmother Godl (75), my Aunts Anya (9) and Olya (18), and Uncle Aron (11) found their unfathomable fate.]

…In August 1942, the Wehrmacht occupied Rostov-on-Don, claiming victory over the Caucasus region, the southern Soviet Union, and the oil fields beyond. In every occupied Soviet territory, including Caucasus, special German action squads, Einsatzgruppen—made up of Nazi (SS) units—moved in rapidly on the heels of the advancing German Army with a mission to establish German order and exterminate the Jews. It was a mission the Nazis executed flawlessly and repeatedly. Of the six million Holocaust victims, nearly one and a half million perished within the borders of the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union. My dearest, Godl, Anechka, Aronchik, and Olya were among them. Nazi soldiers slaughtered them after forcing them to dig their own graves.

Pick up a copy of Last Train to Freedom for more about my family’s losses and survival. Browse historical family photos. Read the letter sent by Olya before she, her grandmother, and her two younger cousins were brutally murdered.

If You Love Thanksgiving, this Story is For You

26

Thanksgiving

November 1984

Most American families have Thanksgiving traditions—from the menu (very traditional vs. semi-traditional with favorite family dishes vs. not-traditional-at-all) to the type of turkey purchased (fresh vs. frozen, self-basting vs. pre-brined, kosher, organic, or free-range) to the method of preparing the bird (roast vs. deep fry vs. bake in a bag or order already cooked) to which family member is hosting the holiday (parents, adult children, or family friends) to what time (brunch, lunch, or dinner) and on and on. Americans have their Thanksgiving traditions down.

Our past, a life of scarcity and long lines, heavily influenced our Thanksgiving customs. Even after living in the United States for over five years, I continued to be in awe of the abundance of the very items and produce that Americans needed to celebrate their holidays, exactly when they needed them. It was the opposite of what I was used to—things disappeared from the shelves precisely when they were most needed. And since you never knew what might disappear tomorrow, stashing whatever you could find was a norm.

With this burdensome mindset, I couldn’t allow myself to put the entire turkey in the oven on Thanksgiving Day and have it be eaten in one sitting. How wasteful! Never mind that year after year, the bird came to us at nearly no cost. One year, I received it as a gift at work; another year, it was free with a fifty-dollar purchase of groceries at a local supermarket; a couple of years in a row, Yan brought home a turkey that was gifted to him at work. Even though every year a turkey found its way to us with little effort, I continued to justify to myself why cooking the bird whole would be careless. I remembered the “Soviet wings” we lived on in Italy and all the dishes we created from them during our two-month stay there. I could make enough meals for a month from a sixteen-seventeen pound turkey. And I did. Grateful for a freezer, whose feature of self-cleaning and its enormous size proclaimed it to be “innovative and futuristic,” year after year, I chopped the uncooked bird into pieces and planned dozens of meals for the weeks ahead.

Standing in the kitchen of our brand new San Gabriel townhouse on the Eastside of Los Angeles, I looked at the seventeen-pound frozen turkey I’d brought home from the market and decided: “1984 is the year we are having a real Thanksgiving—the whole bird is going into the oven!” I had two days to figure it all out. First, I invited Yan’s mother and Sofia with her family to join us for Thanksgiving dinner at five and placed the bird in the freezer, priding myself that I “made it fit.”

Then I delivered the news to Yan and the boys. Yan was thrilled we would finally have a “real” Thanksgiving. Zhenya, who had by then experienced the holiday at a friend’s house, said: “Just don’t make any weird stuff like red-colored potatoes with sugar and marshmallows—I think they are called ‘yams’ or something. They are gross.” Alik launched into a “gobble-gobble” dance he’d learned at preschool, the minute he heard the word “Thanksgiving.” And for one moment, I second-guessed my decision, remembering a phrase from a TV commercial: “It’s her first turkey—it won’t be juicy.” Never mind. I can do this. What I couldn’t have known was that roasting a perfectly juicy turkey would’ve been a welcome challenge in comparison to the one I was about to face.

24 November, 1984—Los Angeles

Hello dearest Mama and Papa, hope all is well, vse horosho.

We received your parcel at the beginning of the week. Zhenya loved another new set of colored pencils and the drafting set. He said, “The drafting set is a grown-up pres- ent.” At nine, your older grandson wants to be treated as a “grown-up.” I suppose that’s not quite accurate—he always wanted to be treated as a grown-up.

The Chukosky book, Moydodyr (“Wash ’til Holes”) was perfect for Alik. Honestly, I hope the story encourages him to wash his hands so his things and toys won’t “run away” from him like they did from the boy in the poem. You should’ve seen Alik’s face when I read: “A blanket ran away, a bedsheet flew away, and a pillow, like a frog, hopped away from me.” He stopped blinking, his already large eyes got bigger, he clenched his favorite blanket (which is always next to him) with his knees, he covered his mouth with both hands, and he froze, staring at the picture in the book depicting what I read. Afraid to scar my child for life, I rushed to the part when the boy ran home and “washed with soap to no end,” and all of his things came back to him. I will report back to you how much the story influenced Alik in keeping up with his hygiene; for now, all I know is that he understood a poem in Russian. I think his Russian may not last too much longer since he spends the day at preschool—where no one speaks Russian.

Last Thursday, we celebrated Thanksgiving. I’ve written to you about this holiday before, but this year, we celebrated it the “right way.” I roasted the whole turkey in the oven and made several of the traditional side dishes: cranberry sauce, green beans, stuffing, and mashed potatoes. And we always thought mashed potatoes were a Russian dish—Americans love their mashed! If you saw the different brands of potatoes at the stores, your head would spin—mine does. I assume American potatoes grow in the dirt just like the Russian ones, but I have yet to see a dirty or rotten potato at a store, not once! I remember digging inside a dirt-filled meshok (cloth bag) to “fish” for potatoes, which were also covered in dirt. Not here. Looks like each potato is cleaned separately and proudly placed on display. Some are packed in different-sized plastic bags for easy pickup and some are sold individually. Who buys one potato at a time? Here is the thing—you can if you want to.

So, I decided this was the year to celebrate Thanksgiving as it was meant to be celebrated, with “all the trimmings,” as Americans say. We bought our first home two months ago (glad you liked the pictures—your room is all set up for you two, and the boys are happy to share a bedroom). Yan and I celebrated our tenth wedding anniversary this month, so it was time for a real Thanksgiving! I ran into a few hiccups with the holiday meal preparation, which I hope will make you smile. Papa may not care about these details but Mama, you will.

First, I didn’t realize it takes three to four days to thaw a turkey. I should’ve known because I had defrosted it in the past when I cut it up for multiple meals, but somehow the thawing time slipped my mind. I could’ve read the instructions on the packaging, but I didn’t. By the way, there are instructions for everything! Every package, every item comes with instructions and recipes—you have to really try to mess things up. So, on Wednesday night, my turkey was still frozen. In a moment of panic, I was ready to cancel Thanksgiving dinner, but luckily I thought of our brand-new bathtub and how it might help save the day. I spent the entire night running cold water over the turkey, turning it from side to side, and by seven on Thanksgiving morning, it was thawed and happy. I know what you are thinking… or do I? Don’t tell me what you are thinking now, because this was not the end of my first Thanksgiving drama. I also didn’t check ahead how long it would take to roast the bird, and when I called Alexandra—my friend and a go-to expert on all things American—at two in the afternoon to ask if it was time to put the bird in the oven for our five o’clock dinner, she got quiet on the other line and then yelled in a panic, “Put the bird in the oven…now!” This was an eight-kilo bird that required six hours to cook, and I only had three. In the end, I made it happen, Mama, but it was quite an event! Now you can tell me what you think of your daughter’s “masterful” kitchen shenanigans. I told the story at dinner, and we laughed the entire night.

That’s all I have for now. Yan and the boys are doing well. They send you hugs and kisses. Yan said he will write to you before the weekend is over, and I am sure Zhenya will have a picture to put in his letter.

You should hear from OVIR soon. Please call us “collect” as soon as you can. We hope it’s a “yes” this time.

How is everyone? How is Misha? Aunt Katya? Write about everyone.

We love you.

Yours, Galya, Yan, deti

With that infamous turkey drama, we began our annual Thanksgiving celebration the American way, except for yams with marshmallows, for which we never acquired a taste. As the number of people at our Thanksgiving table grew year after year, so did the size of the turkey. A twenty-five-pounder became the norm. And a sit-down dinner—regardless of how many people were coming—was a must. Russians don’t do well with buffets; we love our zastol’ye—sitting around the table for hours talking over each other, toasting those who are at the table, those who are away, and remembering those who have passed. That’s just what we do. The “Happy Thanksgiving” toast would always come from Yan. Then, someone would toast me—the hostess—to praise my hospitality and tasty food, za khozyayku! Next would be a toast to the children (grown-up children not excluded)—za detey! To the parents—za roditeley! To the future generation of Americans, our grandchildren—za vnukov! We toast to health—za zdorov’ye! And never to be skipped, a toast of gratitude to America—“G-d bless America”—that one usually would come from me, accompanied by watery eyes with a few tear drops sliding down my face.

No matter what I said, I could never truly express my gratitude. I still can’t. I cry standing up for the American national anthem with my right hand over my heart, holding it from jumping out. I cry when my grandchildren recite “The Pledge of Allegiance.” And I cry listening to Neil Diamond’s “Coming to America.”

Our American friends and family embraced the Russian zastol’ye. Through the years, they added their own touches to the celebration with their favorite dishes. It took me a long time before I became less obsessed with everyone speaking English at the table. Since there were usually multiple conversations going on anyway, why not have them in two different languages?

When my mother finally joined us in America, she quickly became an integral part of Thanksgiving festivities, playing the role of a co-host—or maybe I became a co-host in her presence. It was hard to tell. Her contribution to the holiday table was her famous Russian blinis with red caviar and sour cream; no amount of my protesting her eagerness helped. She ignored me every time I told her that blinis are not for Thanksgiving and Americans hate caviar; she kept on bringing blinis. Mama also took it upon herself to make sure everyone ate as much as they could and then some. She would grab a serving dish, say with potatoes, and walk around the table, squeezing between the wall and the chairs to offer each person more. Not waiting for a “yes” or “no” answer, she enthusiastically deposited a spoonful on the “victim’s” plate, asking “escho?” and added more, regardless of their answer. I tried to interfere with her “hospitality”—painfully familiar to me—embarrassed in front of the Americans at the table, but there was no use. It turned out there was no need. Everyone loved her, and they quickly learned to say “da, escho, Babushka. Spasibo.”

In the meantime, the year 1984 brought…

About the War in Ukraine

January 24, 2023 marks one year since Putin invaded Ukraine, sending 200,000 soldiers toward Kyiv, anticipating capturing the capital in a few days. We know his plan didn’t work, but the war is still raging, with no end in sight. Ukrainians continue to live in terror, awaiting more harm. Hundreds of thousands of lives have already been lost. Men. Women. Children. Where does it end?

I pray for peace in Ukraine.

It’s been more than four decades since I fled the Soviet Ukraine with my husband and our young son to escape the anti-Semitism, oppression, and misery of the Soviet life. Because we wanted to leave, the Soviet government stripped us of our citizenship and our livelihood, and declared us traitors with “no right to return.” We were forever banned from visiting the country that was once our home and where our family and friends remained. Banned from visiting Kiev—the city of our childhood and youth. The city, where we knew every street and every park bench. Banned from ever walking alongside the Dnieper River and swimming in its mighty waters.

Over the years of living in America, my connection to Ukraine and Russia had diminished to, occasionally, being called Russian or Ukrainian by Americans, who equated the country of origin to national identity. The logic was simple. If an American citizen was American, a Russian citizen must be Russian, and a citizen of Ukraine must be Ukrainian. “Such logic had not been carried out in the Soviet Union,” I explained often. “To the Soviets, I was a Jew.” My explanation left people puzzled and at some point, I stopped. So, sometimes, I was Russian, and other times, Ukrainian.

Before January 24, 2022.

In my memoir, Last Train to Freedom, I share why the distinction became important. Read the chapter “Don’t Call Me Russian” below.

Read Last Train to Freedom and step into the world that today captivates millions but remains unknown to many. Walk with me through the streets of my beloved Kiev and let the smell of lilac make you dizzy, enveloping your whole body in its sweet tender scent; watch in wonderment as the Dnieper’s raging waters spill onto the streets of my neighborhood, Podol, as the river basin overflows from the rapidly melting ice. Hold my hand as I grapple with the decision to leave it all behind for a chance at a life of freedom.

Don’t Call Me Russian

April 2022—Los Angeles

Thursday, February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine.

News channels and social media reported that in the early hours of the morning, explosions were heard in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, and Donbas. Kyiv! I dialed my friend, hoping to find out this was all a big misunderstanding and she and her children were safe in their apartment in Obolon District, tucked away from the city center on the left bank of the Dnieper River. I was hoping to hear all was well, as another frigid winter day in Kyiv had begun.

But it wasn’t a misunderstanding. Forty-four million people in Ukraine woke up to a nightmare resembling the old WWII movies I watched growing up in the USSR. It wasn’t a misunderstanding. And it wasn’t a movie. Russian planes flew over the Ukrainian sky as Nazi Germany did in 1941, bombing and burning schools, hospitals, orphanages, residential buildings, and everything else in sight. Russian tanks, marked with signs resembling a half-swastika, rolled through a frosted land that wasn’t theirs, murdering civilians, raping women and children. Destroying lives. Together with millions around the world, I watched in horror the devastation in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Mariupol, and Irpin. The bombings of several train stations as thousands were trying to flee to safety, the explosion at Babi Yar, which vandalized a sacred spot and killed a family of four as they walked nearby holding hands. Ukrainian cities, streets, and sites, once unknown to most outside of Ukraine and Russia, overnight became household names for the most gruesome of reasons.

This is not happening. I can’t fathom it.

I began my memoir by revealing how difficult it was for me to explain my Soviet identity. Russian or Ukrainian? “I am neither,” I said dozens of times. That was what I was told by my country. I was a Jew born in Kiev, then the capital of Soviet Ukraine. But I was no Ukrainian. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union, Americans I came across linked my origin to Russia, and often I didn’t object. Russian. Ukrainian. Whatever was easier to agree to in the moment. Conveying the anti-Semitic logic of Stalin and his totalitarian cohort to free-thinking people was exhausting. And why? They certainly wouldn’t think to identify a Jew differently.

In the USSR, the Russian-Ukrainian identification was the opposite of the Jewish one. Russians and Ukrainians were the same people. Nations-Brothers. Narody-Brat’ya. Most spoke Russian, ate the same food, drank the same vodka, and, above all, used the same profanities with identical, relentless passion. Those who have been following the war coverage probably noticed this sameness by now. Many Russians and Ukrainians had families in both states.

They intermarried with ease. There was no distinction when a Russian dated or married a Ukrainian or the other way around. Now, Russian or Ukrainian dating or marrying a Jew was always noted and often judged. I have never given a thought to which of my friends were Russians and which were Ukrainians. They all knew they were friends with a Jew, however. But that was then.

I have now lived in America for almost forty-three years. I stopped following the politics of Russia and Ukraine a long time ago—I was disconnected from their current events and cared very little about what was happening in the countries of the former USSR. I never believed they would steer toward democracy. Between the Soviet-like Russia’s regime of brainwashing and information suppression, the events of Ukrainian corruption, and reports of increased anti-Semitism, in my mind, very little has changed in that part of the world. And I didn’t care to take sides—I was an American, and those were foreign countries, each with its problems.

My concern grew with America when I noticed a tendency to shut down “unpopular” points of view in the press, on social media, and in the corporate world. When I watched people being attacked and fired from their jobs for expressing their take on policies, politics, and the social aspects of life. I feared we were on the verge of betraying the First Amendment, which guarantees all Americans freedom to speak their mind. It protects those whose opinions we disagree with. Otherwise, it would be pointless to have the First Amendment. I feel compelled to state this obvious point because, now that Russia’s totalitarian policies of information and speech suppression are exposed to the entire world, we must take notice. We must protect America from falling anywhere near the vicinity of such life.

As I write this, it has now been forty-six days since the war began. The recount of atrocities is beyond human comprehension. We may not know the exact number of civilian deaths for a long time, if ever. Nine hundred dead and 1,500 thousand wounded are accounted for so far. Over four million Ukrainians, mostly women with children, have fled Ukraine to neighboring Poland through the only available escape corridor. The lucky ones caught a train that took them part of the way or drove a car until it ran out of gas, walking an additional two or three days to reach the border, with no food or water, under continuous air attacks by the Russian forces. In the thick of the fierce Ukrainian winter, people have run from their homes or what’s left of them with little more than a suitcase and, often, a pet. Many seek refuge throughout Europe; some try to make their way to Canada, Australia, or the United States. Most want to return home someday soon.

In Russia, a twenty-first-century version of the Iron Curtain is coming down hard as those opposing Putin try to flee, while others hide in fear of retribution for thinking outside the party lines (few speak out), and the rest, who believe their vozhd, leader, of the last twenty-plus years, continue to pledge solidarity with Volodya, sing praises to him and Mother Russia, and blame the Ukrainians for provoking the war.

The world I am from is in crisis, the likes of which we have not seen since WWII, and the world at large will never be the same. Today, I have no choice but to reevaluate my position of not caring for either side, and I must choose. Today, when the Russian Army storms through Ukrainian cities and villages, killing innocent people, raping Ukrainian women, and burning their homes, I cry for my beloved Kyiv as if I were Ukrainian. I cry for the Ukrainians and the Russians, who wake up in terror each morning since February 24. I cry for the Jews of Ukraine and Russia. And I take sides.

Next time someone asks where I am from, my answer will be: “I am from Kyiv, Ukraine. Please don’t call me Russian.”